Did you know that San Francisco’s MUNI, the slowest urban transit system in the country, was significantly faster 100 years ago? (Over the past 25 years alone, MUNI vehicles’ average speed has dropped 12 percent.) And it used to be all rail with none of the crawling, lurching buses most of us picture when we think of MUNI today. Did you know that in the 1950s, a schedule of streetcars was not even published because you never had to wait more than five minutes for one, even well into the night on many lines? That’s right, all the way back to the 1910s and up through the mid-50s, San Francisco was criss-crossed with rail lines, each one more frequently running than the next, and the vast majority of San Francisco residents used the heck out of their beloved municipal railway service.

Westbound on Geary approaching Presidio Avenue 1956

Westbound on Geary approaching Presidio Avenue 1956

Photo provided by Jack Tillmany

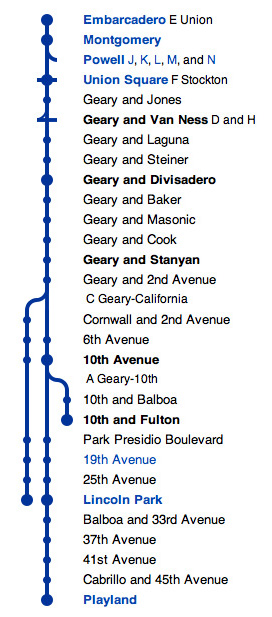

In addition to the J, K, L, M, and N rail lines that we have today, we also had the A, B, C, D, E, a different F, and an H (and briefly a G and an I).

Eastbound Geary at Van Ness, rolling past Tommy’s Joynt and St. Mary’s Cathedral, 1956

Photo provided by Jack Tillmany

Not only that, we also had a number of additional (numbered) lines run by the Market Street Railway Company. (Many of the MUNI bus routes we have today, like the 14 Mission, 6 Parnassus, 31 Balboa, and 21 Hayes, are named after the Market Street Railway lines they replaced.) And on top of all of that, we also had a lot more cable car lines run by the California Street Cable Railroad. And for a while, you could even take a train across the lower deck of Bay Bridge and into the East Bay. In fact, the lower deck was included in the original design of the bridge specifically in order to accommodate rail travel.

Yes, San Francisco was a venerable example of the Golden Age of Rail that directly preceded the large-scale country-wide urban takeover by private cars in the 50’s and 60’s.

In this last period before the automobile gained dominance, trains, trolleys, and interurban lines tied the walking nation along a nucleus of stations and structures. At every stop along Main Street, bars, stores, and so-called taxpayer strips opened…. Vulnerable though these cores would prove, the mobility and urbanity framed by the streetcar and train were extraordinary. Travelers could cross the downtowns of America as fast as they ever would. Foot, bike, horse, carriage, rail–the modes of movement were myriad and harmonious to city making, and designers still did their best to buttress them. — Jane Holtz Kay, Asphalt Nation

Can you imagine a San Francisco in which the various modes of transport were cooperative and complementary rather than competitive? Unpossible! Except that it actually happened.

If you live in San Francisco and you’re reading this blog, the chances are good you’ve experienced the 38 Geary, at least from the outside.

photo by Christian Muñoz

photo by Christian Muñoz

And it looks pretty OK from the outside, right? At least when Christian Muñoz is responsible for the photography. But during peak times near downtown, unless you catch that westbound 38 at one of its first 2 or 3 stops, you can count on watching several of them go by before one with any space for you arrives.

photo by Charles Haynes

photo by Charles Haynes

And once you’re finally on one, you will spend quite a long time wishing you weren’t, and also, if you’re me, wondering how it is the city officials in this Transit First City haven’t done anything about the obvious unmet demand for mass transit along Geary. Do they think downtown San Francisco and its arterials don’t have enough private vehicular traffic? Are they trying to incentivize us to buy cars and cause more congestion? Worse air? More pedestrian deaths? More parking ticket revenue? So they have even more money to not invest in rail for Geary?

By the time you get to the avenues, you might be able to find a seat, and the whole journey is likely to take you 45 minutes to an hour, depending on various things like traffic and whether or not you managed to catch one of the limited stop buses.

Can you believe that there used to be four streetcar lines along Geary? In 1920, it used to take 35 minutes to get from the Ferry Building to the ocean on the B Geary–not exactly HSR speeds but not insignificantly faster than today’s 40-50 minute bus voyage which covers a slightly shorter distance. The A, C, and D lines all travelled along parts of Geary too. I know! Where did they all go? What were the city officials thinking when they got rid of them?

Well that all goes back to a time in U.S. history when rail was being ripped out and replaced by buses in all of America’s major cities. The circumstances surrounding the rapid simultaneous motorization and de-railing of urban America are pretty unsettling, a little controversial (though not quite as controversial as you might expect, given the seriousness of the allegations), and therefore way out of scope for this post. For now let’s just say that for “whatever reason”, the general trend in all of America’s major cities in the 1950s was one of dismantling rail lines and replacing them with buses, and San Francisco followed suit to a point.

San Francisco’s rail came out of this era better preserved than that of most cities for a couple of reasons:

- The fact that San Francisco’s rail lines were half owned, and by the end of 1944, almost completely owned by the city itself made them more resistant to the political undermining and monopolistic overtures happening at the time.

- And perhaps even more importantly, many of the tunnels which were used by San Francisco’s rail lines were not adaptable to car or bus travel, so they were spared the bus treatment. This is why the J, K, L, M, and N lines are still with us today.

The B Geary line, though, was not so lucky. It got ripped out as part of a larger scorched earth campaign of overzealous modernizers in the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency. One of their first projects, Western Addition-A1, aimed to obliterate the “blighted” areas along Geary by bulldozing everything adjacent to it all along the corridor, including a large number of Victorians and treasured cultural institutions, in order to widen it, install a series of superblocks, and create a high-speed boulevard for private cars, patterned after the usual modernist anti-urban practices popular all across the country at the time. And so the B Geary was replaced with buses at the end of 1956, much to the dismay of its regular riders.

B Geary’s last run, Playland at the beach, 29 December 1956

Photo provided by Jack Tillmany

At the time the B Geary line was dismantled, it was very popularly traveled day and night as a direct link between downtown San Francisco and Playland. At the time of conversion, however, the Bay Area Rapid Transit network was already in the planning stages, and the popular Geary corridor was supposed to be included in that network, which would also partially replace the recently demolished Key System in the East Bay.

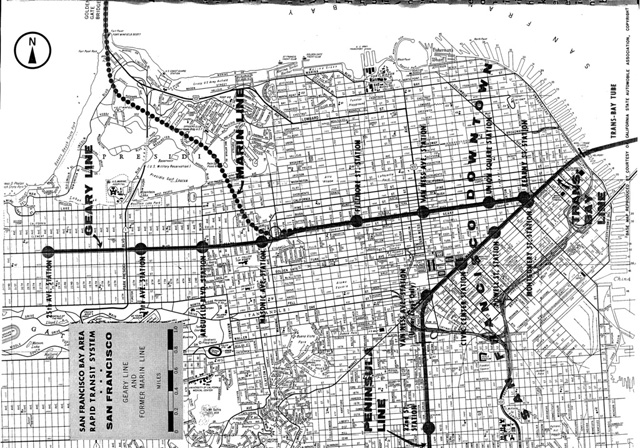

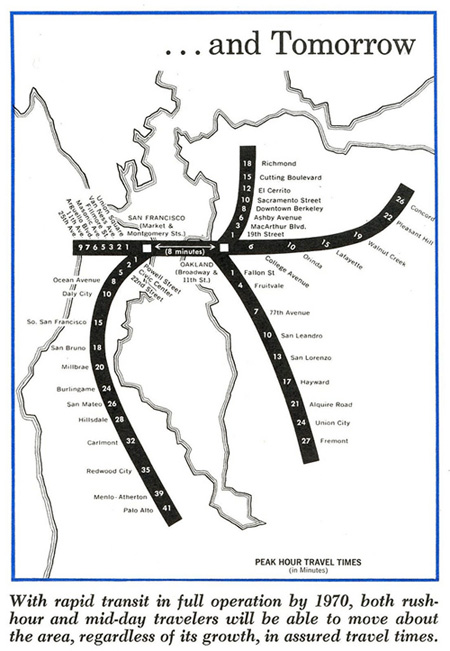

In October 1961, the plan for BART within San Francisco looked like this:

Graphic from Eric Fischer

And travel times on the Geary line were supposed to be around 9 minutes during rush hour from the Bay to the Ocean, leaving both the B Geary and the 38 Geary in the dust.

However, in 1957, Santa Clara County Supervisors opted out of the BART plan in order to focus instead on building expressways. This decision set off a chain of unfortunate events, which ultimately led to Marin opting out of the plan in 1962, apparently taking with it enough of the Geary corridor’s relevance to cause it to fall off the table too.

An effort was made in 1966 to include an underground subway tunnel along Geary as part of a future expansion of MUNI, but the bond measure didn’t achieve the two-thirds majority it needed to pass.

Today, 55 years later, the 38 Geary sees 55,000 daily riders, making it one of the busiest bus lines in the western United States. 100,000 additional riders travel to and from the Richmond District daily on the three nearby parallel routes. Especially considering the disincentives I mentioned earlier, the existing and potential demand for fast, frequent, and reliable mass transit along this corridor is conspicuous. Even now, the number of people traveling on Geary by bus each day equals the number traveling by car. Even so, rapid transit to the Richmond District remains somewhere in the nebulous future.

Current efforts to restore sanity to Geary are taking the form of a planned Bus Rapid Transit line that is still in the review and design stages and won’t see the light of day until at least 2019.

Most BRT lines have real actual separated lanes instead of the fake bus lanes we have in San Francisco.

Most BRT lines have real actual separated lanes instead of the fake bus lanes we have in San Francisco.Photo by Carlos Felipe Pardo

BRT is a form of mass transit in which buses dress up like trains and are let loose on a “track” that’s actually just a dedicated road, and they ride between stations that look just like real train stations, and they pretend all day long that they’re trains even though everybody knows they’re not. The idea is that BRT combines the best features of buses and trains into the ultimate mass transport device: One that’s smooth, efficient, and dignified like trains, yet flexible, inexpensive, and easy to design and implement like buses.

A BRT station in Barranquilla, Colombia. Looks just like a real train station!

A BRT station in Barranquilla, Colombia. Looks just like a real train station!Photo by Carlos Felipe Pardo

The burning question, of course, is this: If BRT is so easy to design and implement, why is it taking until 2019 to get BRT going on Geary even though analysis began in 2009? Some of the delays are of course down to the usual concerns about the loss of parking, the removal of moving car space, the short term and perceived long term disruption to businesses along the corridor, and of course the time honored Level of Service absurdities that still have to be dealt with, but part of the problem is also that BRT does not yet inspire the grassroots transit advocacy that rail does, so the concerns of motorists have not been as effectively countered as they might have been had this been about reinstating a proper railway along Geary.

The BRT project as it was originally conceived also did not inspire the would-be natural allies of transit supporters: bicycle and pedestrian advocates. The concerns of both groups are slowly being addressed as the planning process continues, however the whole effort to achieve a livable Geary corridor could have been a lot more effective and efficient if livability advocates of all stripes had teamed up ahead of time and talked to each other before taking on the customary parking and traffic spill-over remonstrations of the usual motormouths who don’t yet understand the dynamics of induced demand and also haven’t yet figured out that even the existing slow and overcrowded buses are bringing in way more shoppers than that pitiful single-car-occupancy parking spot out front could ever dream of supplying.

In the meantime, even though I’m as disappointed as anyone else that the discussions about planned improvements to Geary are not yet really about rail or bicycles, I have put the next SFMTA Citizens’ Advisory Council meeting on my calendar (Thursday, August 2, 5:30–6:30 PM, 1 South Van Ness Avenue, Room 3074, in case you’re wondering), and I’ll be keeping track of this list for future opportunities to weigh in and provide support for a more livable Geary corridor.

Very well written article. This is clearly an issue that needs to be addressed and I hope more members of the community such as yourself will raise these concerns with SFMTA for those of us not as knowledgeable. Here’s to hoping for a light rail or subway line down Geary one day!